On the Safety of Storks: An Introduction

By Emma Buchman, MOF Digital Content Director & Blog Editor

Emma Buchman is the director of March On Maryland, digital content director of March On Foundation, and editor of the MO Foundation Blog. She also works as a writer and researcher at Studio ATAO. Emma has studied Chernobyl for four years, focusing on the history of the accident and its liquidators. Emma also contributes to a website that collects any and all information on the Chernobyl disaster, specifically sources contemporary to the time of the accident and memoirs from liquidators.

Part 1/11 of the series “On the Safety of Storks”.

— —

Long ago in a galaxy far, far away, I was writing a single article on the revival of wildlife in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone after the catastrophic nuclear accident of 1986. For over four years, I’ve principally focused on the history of the accident and the stories of its liquidators, particularly Academician Valery Legasov and Deputy Minister Boris Shcherbina.

Almost immediately after I began studying, it became clear that there is so much to learn about Chernobyl, that it’s probably impossible to learn all of it in a single lifetime. The Chernobyl story cannot be told completely without touching every aspect of humanity: science, politics, religion, nature, environment, climate, sociology, engineering, and on, and on.

As such, it becomes very easy for Chernobyl research to run away from you with a mind of its own, and the topic of nature and its return to the Exclusion Zone is no exception.

As mentioned previously, this was originally supposed to be one piece on the triumphant return of wildlife and nature in general in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. As I began my research, I quickly became overwhelmed by conflicting opinions from journalists and scientists alike. No matter how much you study Chernobyl, you never get used to the incredulity these paradoxes invoke.

I realized that there is a larger story here that I am supposed to tell; so instead of making the research work for me, I worked for the research. The more I investigated, the more threads would weave themselves together into the story, threads that I felt I could not take out without the entire tapestry falling apart.

This is the final result: a nine part series that covers really all I could hope to cover about nature, Chernobyl, and nuclear power around the world.

Over the next eight pieces, we’ll take deep dives into numerous aspects of Chernobyl’s wildlife. We’ll start with the debate that started it all: how much of a new Eden is the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, really?

We’ll dive into articles from scientists on both sides of the “argument”. We’ll travel over the border to the often overlooked Belarus, which received a lot of radioactive fallout from Chernobyl and has its own area of exclusion.

Once we know the land, we’ll meet the plant and animal residents that are truly thriving in the Zone, visit the Red Forest in all of its irradiated glory, and give a shout-out to the many people who keep the Zone safe and functional.

We’ll then travel to Japan to discuss the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in 2011, its similarities to Chernobyl, and their own wildlife situation.

Finally, we’ll attempt to answer a question from one of the Chernobyl Commission’s most vital members, and see how we as ordinary people can reclaim our part in the everlasting narrative of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant.

Before we dive in, a few quick facts for those new to the Chernobyl story:

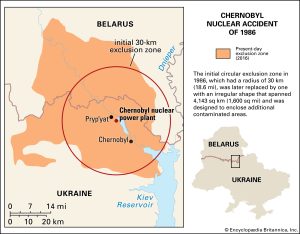

- The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was commissioned in 1977. It is located in northeastern Ukraine (then Soviet Ukraine) near the Belarusian border.

- It had four RBMK-type reactors, and plans were in the works for two more.

- The town directly adjacent to the plant is called Prip’yat. It was established by Viktor Bryukanov and built to house the power plant workers and their families. When it was permanently evacuated after the “accident”, it had approximately 50,000 residents.

- The disaster happened at 1:23:45AM EEST on April 26, 1986 during a safety test.

An explosion blew the 2,000 ton lid of the reactor through the roof of the fourth reactor building. Oxygen rushed into the open reactor and caused a second explosion that concussed the building and shot a column of ionizing radiation into the air.

An explosion blew the 2,000 ton lid of the reactor through the roof of the fourth reactor building. Oxygen rushed into the open reactor and caused a second explosion that concussed the building and shot a column of ionizing radiation into the air. - Multiple factors contributed to the “accident’s” cause. There are scientific causes, direct causes (things that actually caused the physical accident), and systemic causes (circumstances created by the Soviet system that primed Chernobyl and every other RBMK reactor to become a nuclear bomb).

- I’m not a scientist, so I’m just going to recommend reading Midnight in Chernobyl for a true explanation of the scientific causes of the accident.

- The direct causes can be boiled down to mismanagement from the very highest levels of Chernobyl’s leadership which enabled workers to (unintentionally) push the reactor to the point of no return.

- Among the many systemic causes were shortcuts in the design and construction of RBMK reactors, suppressing scientists and other whistleblowers who tried to call attention to these flaws, and a large dose of KGB-level paranoia and secrecy.

- 31 people died as a direct result of the “accident”. This also remains Russia’s official death toll from Chernobyl, unchanged since 1986.

- Firefighters arrived on-scene in less than 10 minutes. Many of them would become victims of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) and die within weeks of the accident. Academician Legasov, a radiochemist and chief scientific advisor of the government commission, highlights their actions as, “not only heroic but very professional, educated, and correct.”

- The total number of people who have been impacted by the radiation from Chernobyl cannot be fully calculated, but the estimates range from the thousands to the tens of thousands. Even harder to calculate would be the number of people traumatized by Chernobyl.

- The disaster was liquidated by an army of scientists, engineers, miners, veterans, government officials, and ordinary Soviet citizens. The liquidation effort was led on-site by the government’s ChernobylCommission. Deputy Minister Boris Shcherbina was its chairman, Academician Valery Legasov was its chief scientific adviser.

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (on the right) in 2013 during the construction of the New Safe Confinement (the dome to the left). Photo credit: Stefan Krasowski from New York, NY, USA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons - There are many aspects of Chernobyl’s story that are dramatized or sensationalized. But don’t let that detract from its horrific truths.

- I hate calling it an “accident” because it wasn’t: it was the hellish culmination of decades of prioritizing profit and reputation over human and animal safety, and those truly culpable for it were able to foist the responsibility on lower-ranking plant workers who really were doomed the moment they came into the Control Room that night, regardless of how irradiated they became.

If this explanation feels incomplete, welcome to the world of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. I hope you’ll come on this journey with me.

Photo credit: Featured photo by Alexas Fotos